ÚLTIMAS NOTICIAS

NOTICIA PATROCINADA

RENOVABLES

Lo que necesito saber sobre…

- Tarifa regulada PVPC y Tarifa de mercado libre

- Qué potencia contrato, periodos de discriminación horaria

- Cómo mejorar la eficiencia energética en casa o en la empresa

- Consejos útiles para ahorrar

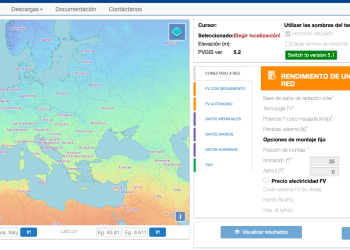

- Qué hacer para poner una instalación de autoconsumo fotovoltáico en casa

- Qué hacer para poner una instalación de autoconsumo eólico en casa

MÁS NOTICIAS

Biovic mostrará en iENER 24 cómo los proyectos de biogás pueden contribuir a la sostenibilidad agrícola y ambiental

El presente y futuro de la ingeniería energética se alza como protagonista del V Congreso Internacional sobre Ingeniería Energética (iENER)...

Soltec suministrará sus seguidores SF7 a un proyecto de OHLA

Soltec ha anunciado que suministrará 130 MW de su seguidor SF7 para un proyecto a OHLA, ubicado en la provincia...

Enagás indica que sus resultados positivos del primer trimestre se deben al plan inversor, al control de costes y al avance del hidrógeno

Enagás ha anunciado los resultados financieros del primer trimestre. El Beneficio Después de Impuestos (BDI) ascendió a 65,3 M€, un...

Aerotermia, aplicaciones y ventajas de la energía verde menos conocida en España

La aerotermia todavía es una gran desconocida en España. Según el Estudio Energías Renovables de SotySolar, sólo un 24,5% de...

Llega el primer Marketplace de hidrógeno verde al mercado de la mano de Lhyfe

Lhyfe, el productor de hidrógeno verde, ha anunciado el lanzamiento del primer Marketplace de hidrógeno verde en su portal Lhyfe...

Opinión pesimista del Tribunal de Cuentas Europeo sobre el avance en la UE hacia las cero emisiones de nuestros coches

La Unión Europea ha introducido el equivalente a una prohibición de venta de coches nuevos de combustión interna desde 2035....

El PERTE de descarbonización industrial recibe 144 proyectos

El Ministerio de Industria y Turismo han informado de que la primera línea de actuación del PERTE de Descarbonización Industrial...

SotySolar suma la aerotermia en una oferta que permite ahorrar hasta un 90% en la factura energética

SotySolar, compañía especializada en energía solar, anuncia la ampliación de su gama de productos con las instalaciones de aerotermia. Un...

La nueva tecnología de purificación de biogás del proyecto europeo LIFE Biogasnet, en el que participa Eurecat

El proyecto europeo LIFE Biogasnet ha desarrollado una nueva tecnología de purificación de biogás que impulsará su aprovechamiento como energía...

IRENA y ACWA Power firman un acuerdo para impulsar la transición a energías limpias

ACWA Power, la empresa privada de desalinización de agua más grande del mundo, es uno de los líderes en transición...